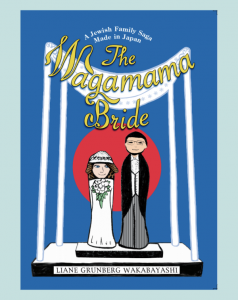

Thank you for joining me here today to talk about The Wagamama Bride, a memoir about my thirty years in Japan. Surrounded by all these books at Pomerantz, I’m excited to talk about something that I haven’t discussed before, the books that inspired me during a nine-year process of writing this book, for in truth, along the way, I needed to find support to keep going. I turned to Torah-connected books that reminded me every single day about the power of words, the power of language, and the power of positivity.

I would say that the daily habit of reading Tehillim, King David’s psalms, became very important. There are many versions of the Book of Psalms and I don’t want to influence you. Many have notations that help explain the psalms in terms of what King David was feeling, and what hardships he was going through, and I related it to my own life. There were many difficult times that I had to write about, and Tehillim helped me accept that going through hard times is part of the human condition. This is what I wanted to convey.

That going through hard times is universal. Spiritual books originating in Torah stories and Biblical heroes offered inspiration to rise above my own limited way of understanding my life lessons. These books offered a fresh perspective, helping me rise above my own particular drama and see the bigger picture.

I want to next share with you some of the books that really helped me. This one which Pomerantz stocks Is called A Lesson a Day by the Chofetz Chaim. The Chofetz Chaim was a great late 19th century rabbi who spoke about lashon hara, about the concept of watching your mouth, watching your speech. This was a revelation. To speak your mind, to say whatever you wanted, without regard for hurting someone else’s feelings or spreading gossip was the norm when I was growing up. Picking up A Lesson a Day, which I found on the library shelves at Chabad House in Tokyo, run by Rabbi Binyomin and Rebbetzin Efrat Edery, I began to realize that the words that I was choosing were not only shaping my destiny but affecting my children deeply as well. And as a writer, I grasped that words that put another person down could do tremendous damage to someone else, as well as myself. This was a revelation, and once I got that, I wanted to understand how to avoid Lashon Hora at all costs.

The Chofetz Chaim was encouraging me to think that by guarding my words, I was learning to reframe difficult memories, and let go of a version of memory that would have cast me as a victim. I was shifting toward being grateful even, and seeing the cast of characters in my life not as perpetrators of grief, but as actors on the stage of life doing their bit to help me grow, to release old patterns, so that I could graduate from associating with their sort of energy.

Now, this may explain too why it took me nine years to write The Wagamama Bride. It took me a long time to figure out how to revisit my life in this way. I’m sure that if I’d attempted to complete the book seven years ago or even five or three years ago, things would have crept into the book that was Lashon Hora, unacceptably harmful speech.

So in my case, I think it took nine years to release the habit of speaking Lashon Hara.

The way to read the Chofetz Chaim is to open to a lesson for the day. The book is ordered by the Hebrew days of the year. It’s a pleasure to start the day by reading a few minutes lesson of Chofetz Chaim, to get inspiration to move the writing for the day in a positive direction and influence my thought process too. A Lesson a Day would help me reframe a story I was writing, to grasp it as a life lesson that was almost a gift to experience, to make me think about the actors on the stage of my story from a different point of view. This was very exciting to me. It helped me get rid of victim consciousness and appreciate the good in many years of family life, which gets lost when even a single drop of character defamation enters the story.

The next book that I highly recommend by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, named by Time Magazine, as one of the top 100 influential people of the 20th century, owing to his monumental life work translating the Talmud into English. This slim volume, one of many other books he wrote based on Torah, is called Simple Words. This book also helped me wake up to the fact that writing was not separate from spirituality, but that writing was actually an expression of the essence of my spirituality. I’ve been a published writer for forty years and in that time, I understood that my words could make or break lives. Reading from the back cover, this is what Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz wrote: “The real quest is to understand the words that we use constantly. For these are the foundation of our existence. What are they? What are they made of? These words, as powerful as they are, are also very foggy. They have a meaning for each of us. But what precisely is the meaning? Clarifying our understanding of simple words will not just change our way of speaking; it will change our way of thinking and change our basic feelings. When we know certain things about those words, we become different people; we are recreated.”

I want to share this message because the healing, the catharsis that goes on when we use uplifting words in memoir writing, fiction, and creative non-fiction writing is hard to quantify. It’s truly life-changing.

The next book I want to share is Happiness and the Human Spirit by Rabbi Abraham Twerski. He was a psychiatrist who introduced me to thinking that a memoir could bring happiness, that the act of writing a memoir could in itself be a happy process. This is what Rabbi Twerski writes on the back:

“To become complete human beings, to find happiness we need to develop our human spirits to the fullest. This is what it means to be spiritual, to be the best we can be; to exercise all the qualities and traits that give us the identity as human beings.” Rabbi Twerski goes on to identify the unique abilities that make us human—our capacity to show gratitude, humility, compassion and generosity.

This was also something challenging to me, to ask myself whether writing could be my path to develop my spirit. Meeting the Chabad Rabbi and Rebbetzin in Tokyo, starting to read the Torah portion weekly, and observing Sabbath were all leading me to want to see my writing as a spiritual activity.

On the bookshelves at Chabad House in Tokyo, I made my first encounter with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, through the book by Simon Jacobson, called Toward a Meaningful Life, in which he boils down everything that’s in the Torah into universal takeaways, lessons for Jews like me who weren’t religious from childhood about what constitutes a meaningful life. For the first time, I felt that the Torah precepts were not only for holy people, but were within everyone’s reach. Reading from the back cover, Toward a Meaningful Life gives people of all backgrounds fresh perspectives on every aspect of their lives—from birth to death, youth to old age, marriage, love, intimacy, and family. The Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, a leader, a sage, and a visionary, proposes spiritual principles that unite people as opposed to the materialism that divides them.

I loved this idea of uniting people instead of dividing them. It became a North Star in the writing of The Wagamama Bride. I asked myself how I could unite my family through the writing of the book even when it was clear that the relationships had to change. The Rebbe’s thinking in Toward a Meaningful Life convinced me it was possible. He didn’t tell me how exactly. But he didn’t need to. Through his example, I understood that he was a bridge builder of the highest order. Connecting Jews to their roots. Building bridges between ultra-Orthodox and secular Jews that had been lost over the centuries. He built bridges too between Jews and non-Jews whenever leaders sought him out.

I’m going to end with one book that came out recently written by Rabbi Mendel Kalmenson, who is the brother of my friend and Rebbetzin Nechama Dina Hendel, of Chabad of Baka, here in Jerusalem, who is wonderful and does have a positivity bias herself. This book, called Positivity Bias, spoke to my heart with the thinking that we can only benefit by looking at life through a charitable lens, looking at people and wanting to see the best in them, and believing that they will rise to the occasion and show themselves in the best possible light. Through reading this book, I could at last grasp how the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the greatest Jewish leader of his generation, was able to take one adverse situation after another and bring hope and miracles.

I want to thank you for joining me here at Pomerantz to hear me talk about the Torah-inspired thought leaders who shaped my frame of mind. Thank you too for taking time out to read The Wagamama Bride and share it with your friends. Many thanks and blessings to you.

Coming Home Far From Home,